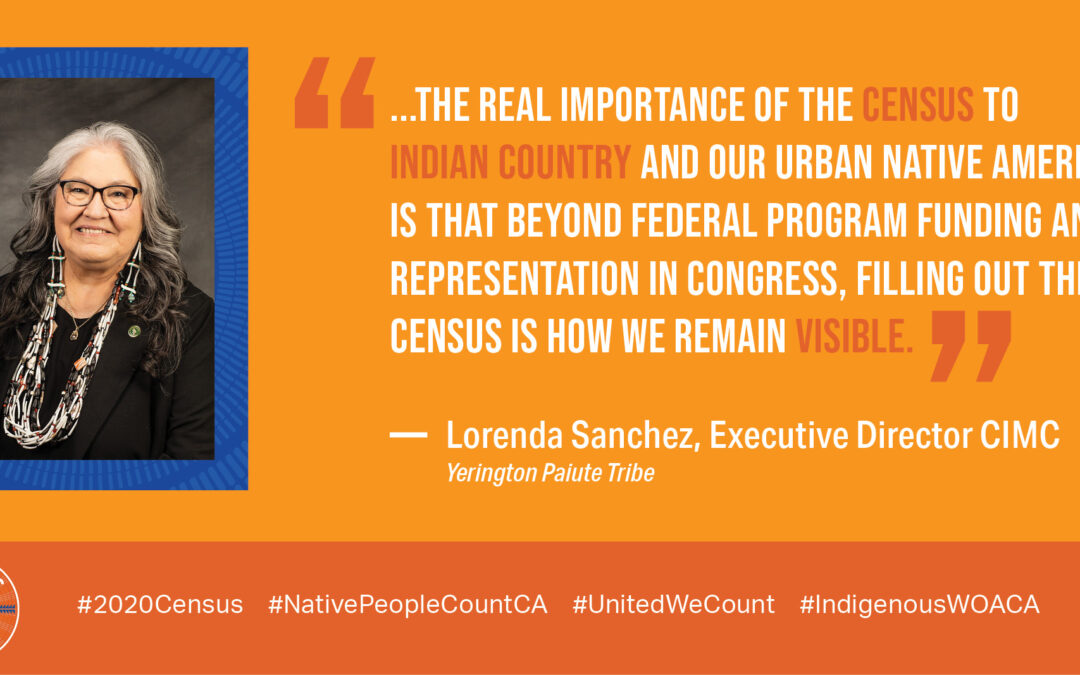

Lorenda Sanchez, Yerington Paiute Tribe, has worked on the last five decennial Censuses beginning in 1980.

She has dedicated over 40 years of her professional life to administering Indian job training efforts and enhancing the lives of California Native Americans.

Since 1977, Sanchez has served as executive director for California Indian Manpower Consortium, Inc. (CIMC). Formally created in 1978 under California state law, CIMC works for the social welfare, educational and economic advancement of its member tribes, partner organizations, and Native Americans living in its vast service area.

Over four decades, the CMIC has trained and mentored hundreds of California Native Americans who now serve in their communities as leaders in all walks of life.

Sanchez also serves on local, state, regional, and national boards advocating for programs and services to address the employment, training, social and economic needs of Native Americans and Native communities.

With unparalleled experience working on the Census, Sanchez brings a wealth of wisdom gleaned over the past fifty years about the Census, how it works, its flaws and its possibilities, and how the data is used to inform government decisions in healthcare, housing, education, and training.

Sanchez says, “I always share with people that the real importance of the Census to Indian Country and our urban Native Americans is that beyond federal program funding and representation in Congress, filling out the Census is how we remain visible. Most people think of Native people as a part of ancient history. We’re only characters in movies and books for many people, and those aren’t always well representative of who we are.”

In 1994, Sanchez read letters written by tribal leaders to the federal government and read original treaties between tribes and the federal government at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

“It broke my heart because the tribal leadership was writing for support for their people that they had been promised through treaties. The letters at first seemed like a request, but with more in-depth reading, the letters revealed they were written as a desperate plea to help their people,” Sanchez said.

She cross-referenced other documents while she was at the archives, and didn’t realize until that time that the treaties include language stating, “…our agreements between the tribes and government will exist in perpetuity ‘until the Indian is extinct.’”

She thought about what she learned all the way home on the east coast’s flight to the west coast. She thought after all these years, how others have tried to eliminate Native Americans as people. “I am amazed at the tenacity of our ancestors and the challenges they went through. We’re still here because of their foresight, but we’re now a tiny population of what we were at their time. The government tried various things, horrible things to eliminate us, to make us extinct, thus removing their treaty obligations.”

After further research Sanchez became convinced, the Census is the best mechanism to count Native people and the only legal way Native people are made visible in the government’s eyes.

From that point, Sanchez committed herself to educate Native communities and work with them to be counted accurately.

She tells Native Americans she meets with that “if we don’t get counted, we’re contributing to the potential of being extinct.”

There was a general lack of awareness in the entire country during the 1970 and 1980 Census and its overall importance. Communities all across the country had an undercount. In Native communities, this helped set the foundation for self-governance and not solely dependent on the federal government.

Sanchez said, “I remember working with and reading articles written by Edna Paisano, a citizen of Nez Percé.”

Paisano was a statistician, hired in 1976 by the U.S. Census Bureau to work on American Indian and Alaskan Native issues, becoming the first American Indian to become a full-time employee.

Paisano visited tribal communities and examined the questionnaire data from the 1980 Census. She found that American Indians and Alaska Natives were woefully undercounted nationally.

Paisano developed statistical techniques to improve the Census’s accuracy. Using rigorous computer programming, demography, and statistics, Paisano and others alerted Native communities to the Census’s importance by coordinating a robust public information campaign.

“In the 1990 decennial, as a result of Paisano’s research and advice, we did a lot of outreach. It was one of the first times that we started to have a stronger count from the reservation areas,” Sanchez said.

But the questions asked in the 1990 Census didn’t take into account mixed households where the head of the household was not always American Indian.

“Native people did not get their true allocation of funding because the numbers were not there for some tribal communities,” Sanchez said.

However, despite its flaws, the 1990 Census revealed a 38 percent increase in the number of United States residents counted as American Indians. This increase was a result of coordinated grassroots efforts encouraging Native Americans to complete the Census.

In the 2000 Census, the U.S Census Bureau provided a more significant investment and interest in Native American communities.

The 2010 Census was the first Census with only ten standard questions. Socio-economic data was no longer collected in the 2010 Census and those after.

There were limited numbers and information collected on employed or unemployed people with different educational levels. As a result, little data was collected to advise federal funding decision-makers for many national programs, including Native communities.

Some tribal communities lost funding, while others gained funding depending on how well they were counted. What followed was a negotiation process between Tribes and federal agencies to hold harmless appropriations funding to Native communities.

They agreed that instead of using the 2010 Census data, the federal government would use 2000 Census data in their funding formulas.

Programs such as the Workforce Investment Act/Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act training programs, the Indian Reservation road program, and housing in the U.S. Housing and Urban Development programs depended solely on Census data from the 2000 Census.

“Most people don’t know, but many of our critical Indian programs for the last 20 years are based on the 2000 Census data. We can no longer live for another ten years on 2000 Census data, and that’s why it is so important to get an accurate count of our communities,” Sanchez said.

Sanchez continued, “This year of the 2020 Census, we have a lot of support with a lot of people willing to share the message.”

California invested heavily in making funding available to reach hard-to-count communities, including Native communities.

In January, CIMC teamed up with the California Native Vote Project and Native People Count California to get the message to California Native Americans about completing the 2020 Census. In August, the Empowering Pacific Islander Communities and Mixteco/Indígena Community Organizing Project joined their efforts in a statewide Indigenous Week of Action for the 2020 Census in California.

The support from California, Sanchez says, has resulted in more people willing to respond to the Census. “I am amazed at the people throughout California that we are working with by opening their doors and opening their reservations during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

When interacting with Native communities in California, Sanchez says the message that resonates most with Native communities in the importance of completing the Census is by graphically showing them the massive loss of funding for education, health, housing, and basic services over the last 20 years and how much more we will lose over the next ten years.

“We need to let ourselves be known; otherwise, we’re always going to be an invisible population. We will always be considered ‘other’ and as an asterisk in a statistical chart. Native people can never be invisible to the point where someone in Congress says that our population is so diminished to be considered extinct, so our sacred lands and everything we hold dear is no longer ours,” Sanchez said.

“We recently produced a promotional flyer for our Native communities, urging them to fill out the Census. We asked a young Native lady to use her newborn baby photo in a traditional cradleboard in the flyer,” Sanchez said.

The cradleboard, Sanchez, says, is a powerful message to Native communities.

“The cradleboard represents our future and keeping our traditions alive. Our Native community members’ decisions on whether to answer the Census or not will determine if our future generations will have a healthy, happy life and a chance at preschool, headstart and educational opportunities to allow our people to thrive over the next ten years.”

###

These interviews and articles are written on behalf of the Native People Count California campaign. For press inquiries or questions, please contact us via email at [email protected].

About NPCCA

Native People Count California is the official California complete count – Census 2020 tribal media outreach campaign. Launched in January 2020 – the Native People Count CA campaign is a collaboration between the Governor’s Office of the Tribal Advisor, the California Complete Count – Census 2020 office, and Tribal Media Outreach Partners NUNA Consulting Group, LLC, California Indian Manpower Consortium, Inc. (CIMC), and the California Native Vote Project (CNVP). Native People Count CA was created with the belief that the 2020 Census is an integral piece to upholding the fiduciary responsibility by the United States federal government to Tribes and its delegated authority to state and local governments.